|

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

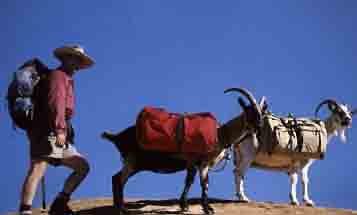

by Yvonne Michie Horn George was the most considerate of hiking companions, adjusting his pace to mine and waiting patiently whenever I stopped to catch my breath. What's more, he actually seemed pleased when I used him as a lunchtime backrest, his soft snoring adding a gentle, vibrating massage to my leaning. All around us lay an incredible chunk of intact wilderness-the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, 2,938 square miles of untracked, tortuous terrain in southern Utah. One must be fearless and nimble of foot to take on its nameless mesas, steep canyons, wind-sculpted pinnacles, and sherbet-colored escarpments. |

|

| Being nimble of foot was true of at least twelve of our group of twenty --- George being one of the sure-footed twelve, along with Frosty, Zuco, Moose, Mo, Curly, Rudy, Alpha, Stripe, Cat, and brothers Precocious and Laser, who endearingly slept cuddled up head to tail. Goats, all. My assessment after five-days of trekking? Don't leave home without one. Goats have been used as beasts of burden for centuries in Europe and Asia, a fact I learned from Wind River Pack Goats' brochure describing their treks into the wilderness, and one that proved useful in quelling friends' tendencies to collapse in laughter when I told them that goats would be our Escalante "sherpas." After my reassurance that I had not confused goats with llamas -- "Yes, goats; not llamas, not mules, not horses, not yaks. Goats." -- most could not resist a parting shot: "Watch your pack; goats will eat anything." |

|

|

Wind River Pack Goats, out of Landers, Wyoming, is among the first of a bare handful of outfitters to use goats as pack animals. Their gradual acceptance into the outfitters' arena can be credited to John Mioncynski, an internationally known wildlife consultant who is widely recognized as the originator of goat packing in America. The idea came to John in the 1970s while following a band of Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep on a research project over terrain too difficult for traditional pack animals to negotiate. John's back was giving out.

Thinking of the dairy goats he kept at home, he began to wonder if they might become more than "barn potatoes." Weathervane, chosen from his herd, with training, proved him right, following faithfully, thirty miles a day, slung with saddlebags. With that, John began a breeding program designed to make the most of goats' natural inclinations to bond easily with humans, and to be strong and hardworking, self-sufficient, and totally at ease in out-of-the-way places. John's stock of pack goats became the nucleus for Wind River Pack Goats. |

|

|

I can't remember how I heard about Wind River Pack Goats. I do recall, however, that I was sufficiently intrigued to see if the outfitter had a presence on the web. It did, with two trekking opportunities offered.

One described traversing Wyoming's mountainous glaciers and snowfields; the other, a fall excursion into the high-desert landscape of Utah's Escalante. Too slippery, too cold was my assessment of the Wyoming itinerary. October in the Escalante, timed to escape the region's searing heat in summer, struck me as perfect, especially given my mental image of deserts as flat. It was the ludicrous notion of trekking with goats, however, not a burning desire to explore the national monument, that brought me to the itinerary's meeting point in Salt Lake City |

|

|

along with five others from as far afield as Seattle and New York City. Charlie Wilson, owner of Wind River Pack Goats, headquartered in Lander, Wyoming, was on hand to greet us. Charlie, with a background as a high school science teacher and leader of wilderness trips for the National Outdoor Leadership School in Lander, would be one of our guides. John Mioncynski, who had preceded us to our starting point in the Escalante with our sherpas, would be the other.

Salt Lake City's urban sprawl soon gave way to Utah's wide-open spaces. Leaving the freeway behind, our route joined Highway 12, a Scenic Byway that earns its fame as one of the most beautiful in the West as it traverses slickrock oceans, sweeps of ranch land, red-cliff canyons, and forests of pine and aspen. |

|

| Cresting Boulder Mountain, we paused at an overlook for a birds-eye view of our trekking terrain to come: the knife-edged Straight Cliffs, the jagged double edge of the Cockscomb, the broad, tilted terraces of the Grand Staircase, with the Kaiparowitz Plateau barreling through like a huge, stone freight train. Two-hundred-million years of earth's history in a grand, 1.9 million-acre nutshell. With a deep gulp I noted with growing dismay that, although we would make our way into what would amount to but an inch on the map of its vastness, there appeared not to be an inch that was flat. Also, given the elevation of Boulder Mountain, I began to wonder how high this non-flat desert might be. I gulped again as my sea-level self heard that we'd be walking at an altitude of five to six thousand feet. I took a good look at my co-trekkers and noted that I was old enough to be the mother of any one. Our inch on the map began in a meadow, lush with the sort of vegetation goats love to munch, which translates to most anything. (Yet another plus of trekking with goats is their ability to be self-catering.) While we transferred our gear into panniers, John and Charlie introduced us to the do's and don'ts of goat packing. Even though they looked like handy handles, instructions were given to never touch a goat's horns. |

|

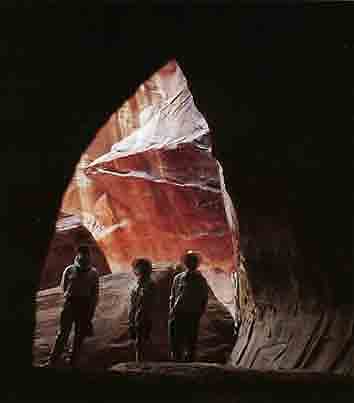

| To do so would tend to remind them that their primal use is to butt things around. "Knoodling," however, the rubbing of chest, cheek, chin, and little knob behind their horns while praising them for a job well done, was encouraged. After each goat was outfitted with wooden X-shaped saddle, a pair of panniers slung over each saddle and securely cinched, we were ready to go. Within yards came our first challenge, crossing the jade-green Escalante River. Off with the boots, on with the water sandals. Goats, which have an innate dislike of water, were knoodled to wade in. The goats, however, were nimbly ascending a boulder-strewn, straight-up, non-existent trail before I was able to re-lace my boots. Slipping, scrambling, panting, and but a half-hour into our adventure, I had an inkling that were it not for the four-legged flotilla in charge of kit and caboodle, I might not be up to this particular parade. Environmentalists rejoiced when Bill Clinton, by presidential proclamation, created the national monument in 1996, one of the largest and wildest expanse of U.S. land to he set aside outside of Alaska. |

|

| While environmentalists clapped their hands, the sparse population that called the area home wrung theirs. The mayor of Boulder, population 150, voiced her concern that five years down the road the town would be nothing but phony trading posts, motels, and pizzerias. Boulder's main claim to fame, before finding itself as a gateway to a national monument, was being the last town in the United States to be reached by road. When that happened, in 1938, there were those who decried the road as leading to the end of their world and who would have preferred mail to continue to arrive by pack mule. On our one-minute tour through Boulder on Highway 12, enroute to our starting point, it appeared that, despite the mayor's concerns, little change had occurred in Boulder. |

|

| By day two, my body had come to an agreement with the altitude, concern for my dignity had departed with a decision to descend steep inclines via the seat of my pants, and I'd learned to choose a site out of view of the others to pitch my borrowed tent so as to not publicly audition for America’s Funniest Home Videos. As for the goats, they'd settled into their roles. George, for example, was described by John as the "social director," constantly checking to be certain that everyone was accounted for and making little bleats and moans when all was not right. Alpha, worrywart and wary, was the "watch goat," found on the highest point above camp, keeping an eye on everything. Each wore a little tinkle bell around its neck. At night, awakened by rustlings around my tent, I felt my heart stop pounding when I heard the sound of soft tinkling-not a mountain lion, not a rattlesnake, just one of the gentle goats on people patrol. Each day's journey ended at a site with nearby water, a sheltered spot to establish a "kitchen," and a choice of secluded places where tents might be pitched. From panniers appeared makings for meals, prepared by Charlie and John. Yet another pannier held John's 100-year-old Hohner accordion, from which emerged cowboy laments, Swiss yodeling tunes, and "goat songs," melodies composed by John incorporating plentiful up-and-down runs of notes, a musical style admired by the goats. The goats had favorites, we decided, as they created a shadowy, appearing-and-disappearing audience around the campfire. |

|

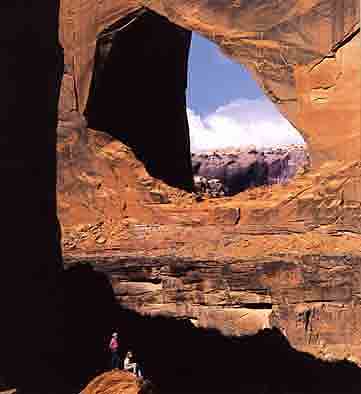

| We met no other souls in our five days of trekking. With developed trails all but nonexistent, by whim and wind we made our way over slick-rock expanses, idled while the goats ate their fill in willow-rich oases, clambered up to leave-you-weak-in-the-knees views from sandstone table tops, and crossed numerous creeks and rivers rushing on their way to Lake Powell. Surrounded by solitude and space, it was as if we were the first to enter the monument's dramatic geology -- although that was far from true. Man has left his mark in the Escalante for at least 8,000 years. People of the Fremont and Anasazi occupied the area for several hundred years, leaving behind petroglyphs, granaries, and dwellings. |

|

| Paiute, Ute, Hopi, and Navajo also left evidence of their presence. Mormon pioneers created a history of migrations and abandonments beginning in the 1860s. The tiny towns of Tropic, Escalante, and Boulder, existing today on the edges of the monument, were founded by Mormon ranchers and farmers. In the 1950s, prospectors came to the area in search of uranium. Our parade of goats and people -- but dots on the monument's enormity of space and time -- was no different. We, too, like all gone before, were only passing through. Northern California writer and photographer Yvonne Horn is a frequent contributor to ODYSSEY |

|

The Grand Staircase-Escalante

National Monument is a dramatic, multihued landscape rich in natural and human history. Managed by the Bureau of Land Management, the monument represents a unique combination of archaeological, historical, paleontological, geological, and biological resources. Few roads lead into the monument; high-clearance vehicles are recommended. No services are available inside the monument. Outfitters must obtain permits to enter the Monument. The Bureau, can provide a list of others in addition to Wind River Pack Goats. For information, contact the Bureau of Land Management's Interagency Office in the town of Escalante, 435/826-5499. Current information on the monument, road conditions, maps, and hiking information are available. Easily accessed is the Calf Creek Recreation Area, off Scenic Byway 12, 15 miles east of Escalante. The area includes a 5.5-mile round-trip nature hike to Lower Calf Creek Falls.

An untrammeled gem, the monument stands in stark contrast to its famous neighbors, some of the country's most popular and heavily visited national parks and recreation areas: Grand Canyon National Park, Glen Canyon Recreation Area/Lake Powell, and Bryce and Zion national parks.

Wind River Pack Goats, 280 N 9th St., Lander, WY 82520. Phone: 307/332-3328; e-mail: cwilson@goatpacking.com; online: http://www.goatpacking.com. Offers spring and fall excursions. Meeting point: Salt Lake City. Cost: $1,490, includes transportation to and from Salt Lake City to the starting point in the monument, and all meals on the five-day, six-night trek. (The sixth night, an overnight in Boulder before returning to Salt Lake City, is not included.)

The Pack Goat, by John Mioncynski, is an entertaining, informative read. It is currently out of print, but available used at http://www.amazon.com